We love carbonara as much as we love history! So in addition to sharing the recipe with you, which you can find here, we’d like to chat about the fascinating history of this tasty dish. Its origins are shrouded in a

veil of mystery, with numerous legends and hypotheses surrounding its birth, all of which can be read below.

TextbooksBut first off, we need to start with the facts. There is one reliable method for reconstructing the history of a culinary dish:

cookbooks. And we have done just that! By sifting through the pages of old magazines and recipe books, we can now let you in on the origins of one of Italy's best-loved dishes, both home and abroad.

In 1925, our beloved chef Ada Boni published a famous cookbook. Entitled

Talismano della Felicità, and long-considered the “sacred book” of Italian cuisine, it is available in English as the

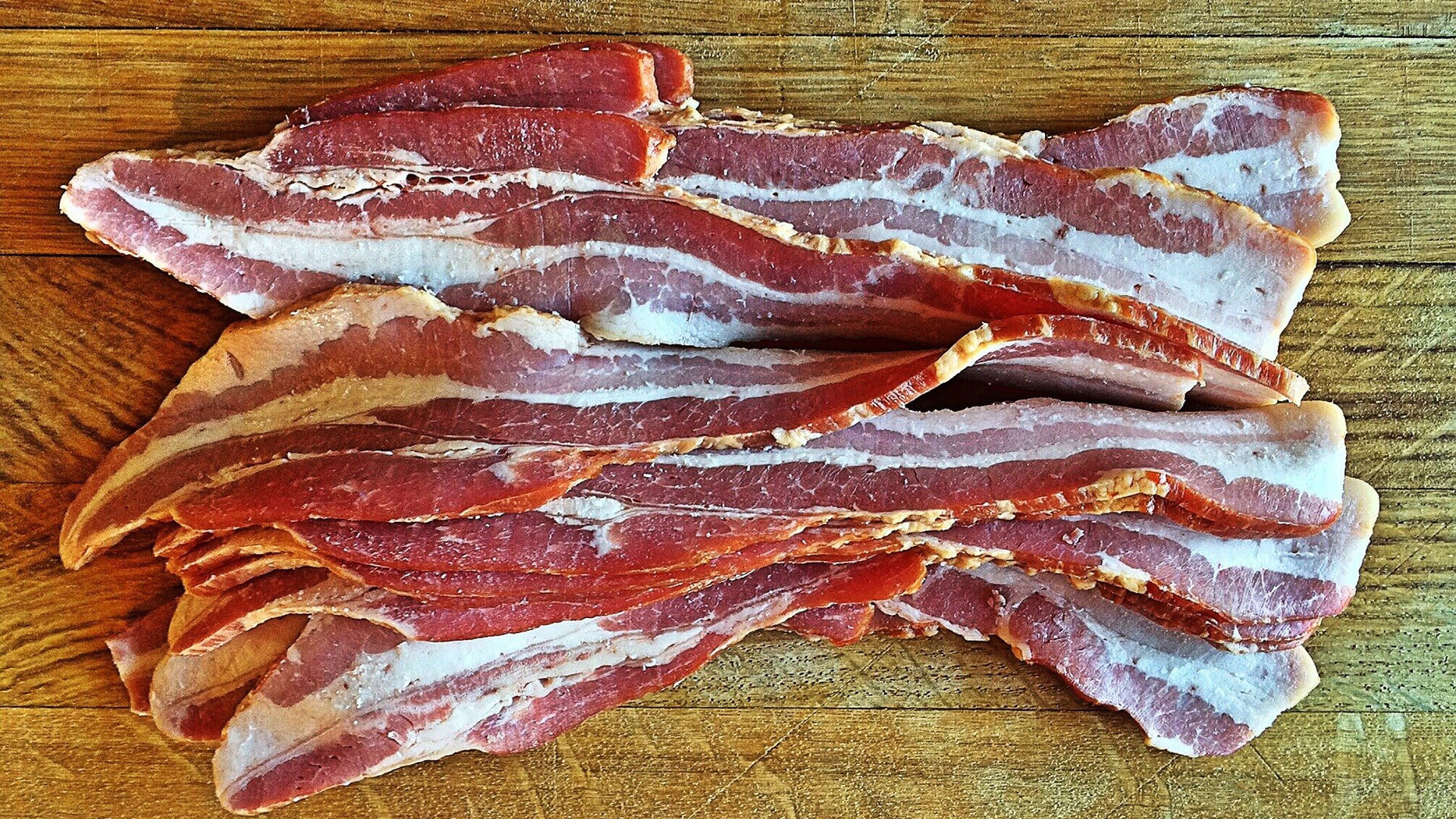

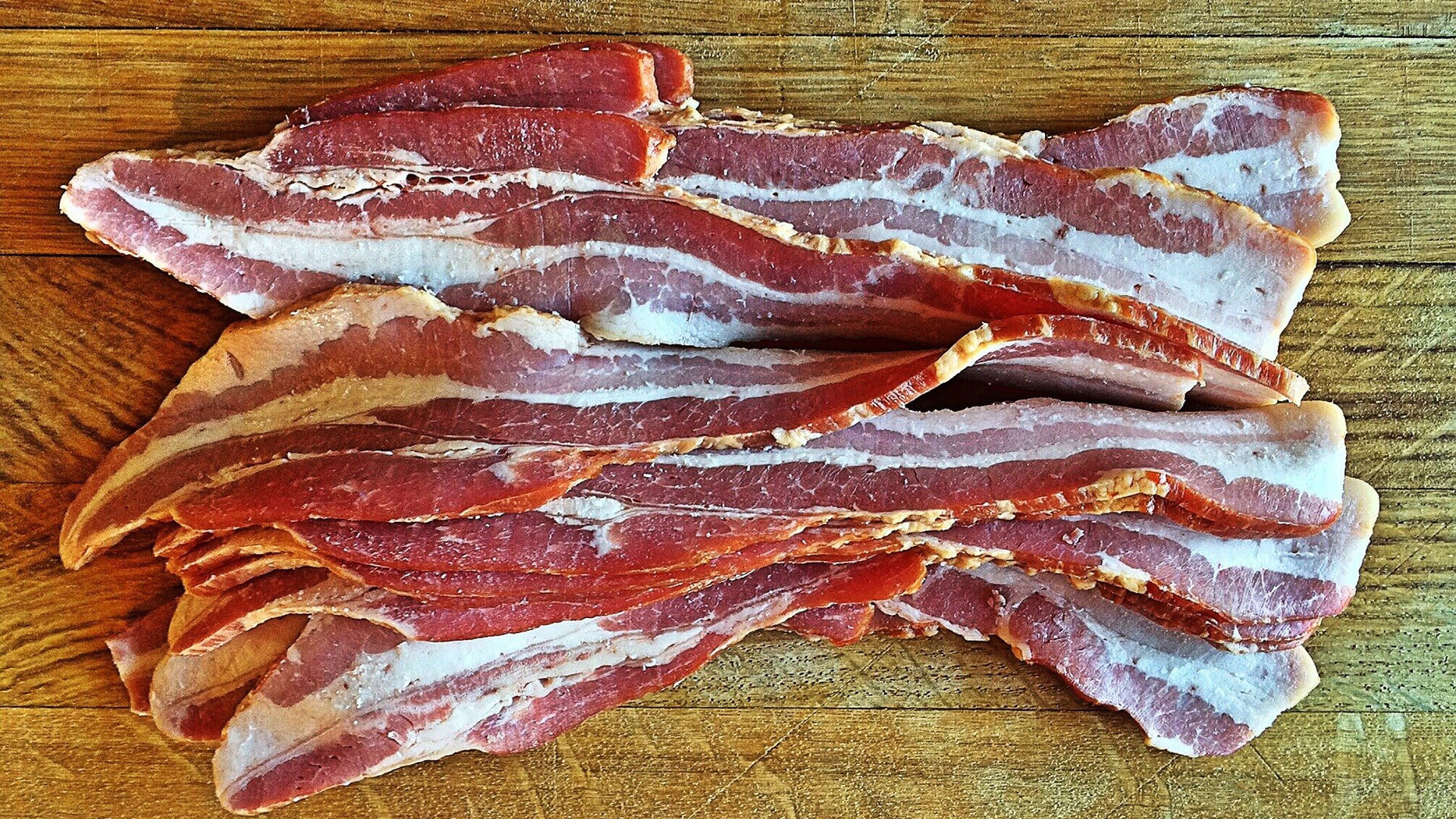

Talisman Italian Cookbook. Carbonara is curiously missing from its contents. Yet carbonara is a typical Roman dish, and Ada was from the Eternal City. According to the famous Roman writer Livio Janattoni, there was no trace of this dish in the 1930s, and its first mention dates back to 1944 after Rome was liberated by US troops. Many claims it is because of these troops and their typical

American-style breakfast that carbonara was born. First off, the recipe calls for bacon, which is not typical of Rome region, where traditional recipes like Pasta

alla Gricia or

Amatriciana call for

guanciale, which is made from pork jowl (and not smoked pork belly, as it’s the case of bacon). Marco Guarnaschelli Gotti, the cultivated author of the Great Encyclopedia of Italian Cuisine, states that at the end of WW II, among the few resources available there were “military rations distributed by Allied troops, which included powdered eggs and smoky bacon. Some unknown genius had the idea to use them in a pasta sauce.”

The first recipe for carbonara appeared in 1952, not in Italy, but in a Chicago’s restaurant guide. In a review for a restaurant named Armando's, the book's author, Patricia Bronté, included a recipe for one of the dishes served there — without doubt, it is the same as the carbonara we know and love today! In Italy, the first recipe of a similar dish was printed in the August 1954 issue of the magazine The Italian Kitchen, however it is far from the recipe considered “authentic” today, as it uses garlic and — trigger warning: purists should look away now —

gruyere cheese. The following year, the recipe judged today as “the true” carbonara made its first appearance in an Italian cookbook, and it was officially consecrated as a national Italian dish in Luigi Carnacina's 1960 milestone work:

Great Italian Cooking.Maybe from Abruzzo region?But let's turn back to the 1940s for a bit, because there's another hypothesis on

carbonara's origins that the Walking Palates team particularly likes, as it concerns our home region of Abruzzo! This theory's merit lays in offering an explanation for the name. The dish is said to be related to coal workers — called

carbonari in Roman dialect —

from Abruzzo and the Apennines. They brought with them ingredients that had a long shelf life, such as eggs or smoked

guanciale, to be used in their daily meals during long days spent watching over charcoal kilns. Moreover, recipes of the kind known as

Cacio e Ova (Cheese and Eggs) are extremely popular in Abruzzo’s cuisine. One story states that Allied soldiers fell in love with this dish sometime between 1943 and 1944 while stationed on the Gustav Line, a German line of defense that prevented the Allies from reaching Rome. It stretched across the Italian peninsula, cutting Abruzzo in two. The typical Abruzzo dish was adapted to Allied soldier's tastes by swapping in American-style bacon, and the result was a comforting bacon-and-eggs meal that reminded them of home.

Or Neapolitans?A final theory links carbonara to Neapolitan cuisine. It

emerged recently in some cooking magazines and was also broadcast on a famous Italian TV show. A

traditional Neapolitan technique adds a mixture of beaten eggs, cheese and pepper to the final stages of a dish's preparation, much like in carbonara. This technique is used in many Neapolitan recipes and was mentioned in Ippolito Cavalcanti's famous cookbook from the early 1800s. This mixture is used to prepare so-called “vegetarian carbonara” recipes, such as Pasta with Peas or Pasta with Zucchini, as well as in meat-based dishes, as for instance

Tripe alla Pasticciola. Even if this is an interesting theory, it doesn't explain the name or why the dish is normally linked to Rome instead of Naples.

Yet surely Roman!Whatever its true origins, Romans quickly adopted carbonara as their own, and there is no one who would

dare question this. This dish made its film debut in the 1951 Italian motion picture,

Cameriera Bella Presenza Offresi... In the movie, a maid, played by Elsa Merlini, is asked by a potential employer during a job interview, “Sorry for interrupting...but, listen, do you know how to make

spaghetti alla carbonara?”

The classic recipe that we all know and love consists of

four simple ingredients: pecorino cheese, pancetta, eggs and pepper. It is most often served over spaghetti or rigatoni, and in Rome,

guanciale is often substituted for smoked

pancetta.

And not always "pure"The recipe's huge popularity at home and abroad has spawned

innumerable varieties. There are versions by famous chefs, as well as others that use local ingredients. For example, it is hard to find

pecorino in many foreign countries, and it is often prohibitively expensive. Eggs are sometimes substituted with cream to accommodate trends (such as in 1980s Italy), or local tastes (cream is a very popular ingredient in French cuisine). Not to mention, many people are afraid to use raw eggs. To the consternation of purists, there are also versions that incorporate white wine, garlic, onions, parsley, chili pepper and much else that a chef's imagination can come up with!